objectives

Use expected value to understand why someone might engage in crime.

Consider the moral implications for actions, even if the expected value is positive.

time needed

20-25 minutes.

materials

The ability to show the comic panels and video Vulture begins a life of crime.

Excel file for criminal behavior.

A six-sided die.

overview

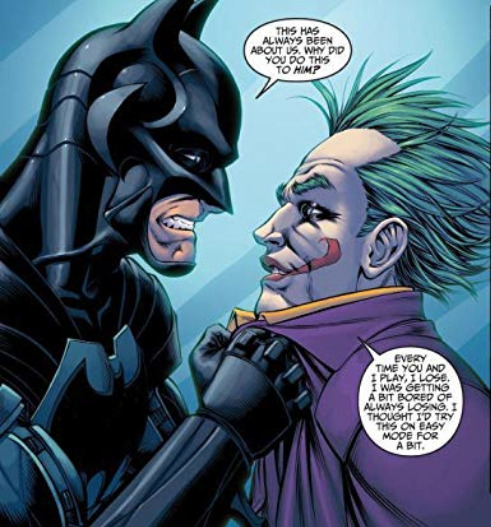

When someone engages in a crime, our first response might be to think they are not behaving rationally. This is particularly true in the comic world. The bad guys never win. Even when they think they’ve succeeded, the hero usually turns the tables on them. One exception to this occurs in the DC story Injustice: Gods Among Us. The story kicks off when the Joker leaves Gotham City and heads to Metropolis where he confounds Superman into killing Lois Lane and their unborn child. Superman goes off his rocker, understandably, and Batman is apoplectic. Joker explains his unprecedented move by saying “I was getting a bit bored of always losing”.

Joker keeps trying to take down Batman, even after acknowledging that he never wins. What drives such dedication to the cause? It could be insanity, or maybe Joker understands something about the economics of crime. Gary Becker’s work on crime points out that criminals are not all as crazy as the Joker. They may not sit down at the kitchen table and work out the math, but criminals often weight the costs and benefits of crime. What are the penalties if caught? What is the probability of being apprehended? What is the reward for a successful criminal enterprise?

In the comic world, there are some obvious problems with the justice system that incentivizes criminal activity. For one, the prisons are revolving doors. Most criminals are able to break out whenever they want. Another problem is that the punishment for even the worst crimes are notoriously light. Only one criminal in comic history was ever executed, Mr. Mind, and he was literally a worm. Furthermore, there are so many criminals that it is relatively easy for some bad guys to slip through the cracks. Even if they are caught, the court dockets are so clogged up it is likely any case that makes it to trial will result in inadequate penalties. As a result, in the comic universe, the cost side of the expected value equation is likely to be lower than the benefit side.

To this end we can see how a normal guy might turn to a life of crime. Adrian Toomes is engaged in a cleanup operation for the City of New York in Spiderman: Home Coming. In this clip we see the legitimate businessman being told his services are no longer required. As a result, he reconsiders his life choices and enters the criminal world as the Vulture, selling alien tech based weapons to bad guys.

Toomes’ quick calculation is more formally demonstrated by expected value where:

Expected value = [(1-p) x Payoff] – (p x Fine)

p = the probability of being caught

(1-p) = the probability of not being caught

Payoff = the reward for a successful criminal activity

Fine = the punishment you receive if you are caught

The equation says that the expected value of choosing to commit a crime equals the probability of not being caught (1-p) times the value gained from success (payoff), minus the probability of failure (p) times the costs you bear from the failure (fine).

In the case of criminal behavior, if the expected value of the crime is positive, then it is rational to engage in that behavior.

action

Ask students if they’ve ever thought about committing a crime. No need to get into the details of course, but ask them what stopped them or encouraged them. For many who didn’t go through with it, the threat of the punishment was enough. For others, especially the less sneaky ones, the probability of getting caught was too high.

Those who did commit the crime probably felt that the benefit outweighed the cost. (Even if they don’t confess, it is worth explaining this position.) The value of whatever action they took was either very high, or the probability of being caught was low, or it was some of both.

To help students visualize the decision making process, show the video Vulture begins a life of crime. Now, proceed through the following question. Use the Excel table to assist your calculations.

a) Assign your students one of the sets of values corresponding to the 10 options in the table and have them compute the expected value of committing a crime. Does it make sense for them to do it? Some will have a positive value, others will have a negative value. It might be worthwhile to tell your students that the assumption is that they are behaving rationally as some students may want to commit the crime just for fun. Perhaps add a positive incentive for choosing correctly.

b) Now, reduce the fine so that all expected values are positive (a suggested level is provided in the table), and ask students to recalculate the expected value. This equates to the short time a super villain spends in prison. Would students rethink their stance on committing crime?

c) Now return the fine to the original level and reduce the probability of being caught so that all students once again have a positive expected value (a suggestion is also in the table). Once again, ask students to recalculate the expected value. This happens in comics when the local police are stretched thin and the chances of being caught decrease.

d) Finally, return all values to the original levels. When a superhero enters the scene, they alter the probability of getting caught. Presumably it is less likely that the criminal will get away with their crimes. However, not all superheroes are equally adept at stopping the bad guys. Presume a new superhero enters your town. Using a six-sided die, determine how powerful this hero is. Roll the die. Whatever number comes up increases the probability of being caught by that number divided by 10. For instance, if you roll a four, the probability of being caught increases by 0.4. Now have your students compute their expected values. If they still have a positive value, they are your supervillains!

discussion

Expected value is a way to show why someone might engage in crime, but clearly there are other influences at play. Making a decision like this solely on the numbers removes the moral factor that is part of the choices we make. It is worth mentioning to students that just because the numbers work out, doesn’t mean you should do it.

Question:

Ask students what else might be part of the decision to engage in crime. What makes it difficult to include these things in an economic calculation?

Answer:

Some of the suggestions will include: insanity, desperation, immaturity, peer pressure, bad information, drugs, and the lack of a moral compass. These are difficult to include in determinations of why people commit crimes, because they fall outside the expectations of rationality.

Question:

Presuming we want less crime, what kinds of actions could a city or municipality take to achieve that goal? Do you want these things implemented where you live? Why or why not?

Answer:

Based on the expected value calculations, you could raise the penalty, or increase the probability of being caught. This likely involves spending more resources on the police and the judicial system. Doing this requires a reconsideration of how money is spent. Do you want more police if it means the roads don’t get fixed, or fewer teachers get hired or the park system falls into disrepair? More police might make you feel safer, but how many is too many?

Question:

Do you want to be as safe as possible?

Answer:

This is a little tricky. We want to feel safe, but if that means lots more police on the street or cops sitting in their squad cars waiting to pull you over for the slightest infraction, maybe being safer is not the greatest thing. Making you safer involves tradeoffs. What are you willing to give up to be safer?